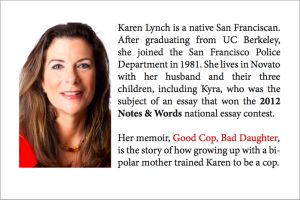

Karen Lynch tells the true, humorous and poignant story of one young woman’s journey from Haight-Ashbury flower child, to homeless teen, to pot-smoking college student, to Renaissance serving wench, to her eventual new family in the San Francisco Police Department.

The enmeshed relationship of mother and daughter has been explored in scores of books, most famously, “My Mother, My Self” by Nancy Friday. My memoir is the story of one woman’s journey to free herself from the manipulations of her narcissistic, mentally ill mother.

Though I didn’t fully realize understand all of my reasons at the time, in 1980, shortly after the San Francisco Police Department began recruiting women patrol officers for the first time, I found myself curiously compelled to be a cop. Years later I began to consider the possibility that not only had fear of my mother unconsciously compelled me to arm myself, but that my mother had inadvertently trained me for the very job I grew to love.

Prologue

“Graduates Face Worst Job Market Since Great Depres- sion.” The headline of the San Francisco Chronicle caught my eye while I was waiting for the bus. It was June 1980, and the day’s top news story was a depressing reminder that my newly issued college diploma was a useless souvenir of four ambling years.

I put a quarter in the box, dug out a paper, and was skimming the news when an ad stopped me cold. Four uniformed women smiled at me above a caption ordering, “Join the SFPD.” The women looked proud and confident, part of a big, happy family. I felt a surge of envy. I’d spent my childhood yearning to be part of a family. For a moment, I tried to envision myself belonging to this group of uniformed sisters.

Then I imagined how Mom would react if she saw the ad. I could almost hear her outrage: “Look at those storm trooper sell- outs. Now they’re using women to protect the capitalist pigs!”

I was on my way to Fisherman’s Wharf to work my shift as a serving wench at Ben Jonson’s Olde English Taverne. Wearing a revealing costume and showing my cleavage for tips had been a lucrative, if sometimes humiliating, way to pay for my last year of college. I had natural double Ds and wasn’t afraid to use them. But I’d never intended to make a career of it.

The dismal job market meant that the prospect of spending the rest of my life as a serving wench in a Renaissance-themed bar was a horrifyingly real possibility. I pictured myself decades in the future, gray haired and shriveled, my sagging breasts flop- ping inside my corset as I leaned on the table for balance and cackled, “Now, which of you kids ordered Galahad’s Grail of Grog? Who had the Maid Marian’s Mead?”

But being a geriatric wench was not a realistic career choice. A large corporation had recently purchased the tavern, and the management intended to close us down. Then what? I had no safety net, no family to take me in, and no marketable skills. My biggest fear was ending up homeless again.

I walked from the bus stop to the Cannery, unlocked the dressing room door, and stuffed myself into my two-sizes-too- small green velveteen corset. I knotted my burlap skirt high on the hip for optimum leg viewing, then checked myself in the mirror and noticed an ugly beer stain on my skirt. I tried imagin- ing myself instead in one of those crisp blue police uniforms, but dismissed the ridiculous thought of someone like me becoming a cop.

I had grown up in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood as the Summer of Love dawned in San Francisco. Mom had abandoned her East Coast family, fleeing them as if running for her life. She spent many years on government assistance because of her illness—manic depression with overtones of paranoid schizo- phrenia. She seldom mentioned her New York family, but during episodes she occasionally ranted in public about her awful parents, lashing out at strangers, insulting and terrifying them. Sometimes the police came and took her away. I was glad to see the police, but Mom hated them.

One of my biggest fears was that I’d end up like her; depen- dent, reliant upon the Department of Social Services or the gen- erosity of some boyfriend to keep me alive. I had learned from an early age that relying on the kindness of strangers was a risky business.

In her lucid days, Mom had always insisted I should become a nurse. She had attempted nursing school herself as a young woman, but her education had ended when she had what she described as her “first nervous breakdown.” Maybe she hoped that if I achieved her goal, it would redeem her in some way. Or maybe the lines between us were just so blurred she couldn’t see me at all. And for my part, I suppose I believed that if I did everything she asked, Mom would finally be happy.

For four years I’d given Mom’s dream my best shot, scram- bling for Cs in chemistry and physiology and failing organic chemistry twice. Now I had graduated from college, and in spite of my terrible science grades, I had been tentatively accepted into the fall class of nursing students at Emory University in Georgia.

The university required I take organic chemistry yet again in summer school and this time get at least a C.

The school had optimistically sent me a box containing a nurse’s cap, stethoscope, and name tag. When I put everything on and examined myself in the mirror, I cringed. I hated the ugly cap, and the harsh squawk of my name tag, Nurse Nassberg, recalled Nurse Ratched from One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

With the cap propped on my dark bun and my cheekbones free of makeup, I looked severe and a bit scary.

Summer school organic chemistry was proving to be no easier than the regular session had been. Every day before my wench shift, I walked into a classroom in which the professor might as well have been speaking Hungarian. I was failing again, and beginning to face the fact that I would never achieve Mom’s dream. All I had ever wanted was for her to be proud of me, and now I felt overwhelmed with the anticipation of her disappoint- ment. I tried rehearsing how I would break the news to her and could already hear her in my head: “The state sure wasted that scholarship money on you!”

On my day off from the tavern I distracted myself by brows- ing City Lights Bookstore with my childhood friend, Monica. Monica and I had known each other since second grade, and she had stuck with me through everything. She was strikingly beauti- ful, with caramel-colored skin and long, wavy, golden-brown hair.

I hoped Monica would help me bolster my courage. I had decided not to bother returning to chemistry class, and I knew I could only delay breaking the news to Mom for so long. I would give myself one more day before making the dreaded phone call.

As we came out of the bookstore, we passed Vesuvio Cafe. Although my parents had met there decades earlier, I couldn’t remember ever stepping inside. But that day, I felt magnetically drawn in. We chose a table by the window looking out over Columbus Avenue. When our Irish coffees came, we toasted our mysterious futures.

Then suddenly there she was, a young woman with wavy, dark hair driving a black-and-white patrol car up Columbus toward Broadway. She was wearing a San Francisco Police Department uniform and smiling like the women in the ad.

“It’s me, Monica. Look! It’s me!” I gestured out the window. Monica looked out in time to spot the rear end of the cruiser.

She turned to me and scrunched her eyebrows.

“I know it sounds crazy, but I just saw myself driving that police car! I was wearing a uniform! Monica, I think that’s what I’m supposed to do!”

“Whatever floats your boat, honey,” she said, toasting me again.

“Women have no place in police work,” barked the man at the next table. He downed his beer, grinned, and moved in closer.

“Let’s go, Monica.” No doubt the loudmouth thought he was discouraging me, but his words only made me want to prove him wrong.

For the rest of that day and the next, that woman officer, who would soon end up playing an important role in my life, stayed on my mind. It felt so right. The universe had struck me with a lightning bolt, and for that moment my destiny was clear.

I began searching the paper for stories about the new female cops, trying to learn as much as I could about them. Women had been working as patrol officers in San Francisco for only a few years, and the Chronicle periodically ran articles reporting on the progress of the rookie females. When the public was polled, few men interviewed thought women could survive as street cops. Some said females were too weak and emotional to handle the stress and predicted the women would run and hide when they were required to fight with a criminal resisting arrest. I felt offended. I was stronger than some of the men I knew, and I had learned to control my emotions, at least outwardly, after years of managing my volatile mother.

The San Francisco Police Officer’s Association was energeti- cally fighting the court order compelling the city to hire women. Mom had weaned me on feminist philosophers like Simone de Beauvoir and Gloria Steinem. Now my pride was compelling me to prove the naysayers wrong. I reasoned that if women wanted equal rights, we would simply need to prove we could do the things men do.

But even as I gained certainty about applying to the depart- ment, another part of me wondered what the hell I was think- ing. My hippie family tribe had lived their lives avoiding the cops. Monica had been my friend forever and would never disown me, but what about my other friends? What about the friends I’d smoked pot with in college at Berkeley? Would they see me as a sellout or traitor? And was I even the sort of woman the police department was looking for? Would the men see me as a joke? Could a former serving wench with 36 DDs walk a beat in the Tenderloin?

Ultimately none of these considerations stopped me. I just couldn’t let go of the idea that I was supposed to become a cop. I filled out an application card, and soon the city sent me a packet of information.

The testing process to get into the police academy was three- fold—fourfold if I included the challenge of telling my mother I wanted to be a cop. My first hurdle was the written test. Close to a thousand people were competing for a couple hundred posi- tions, and I had to scramble to find a vacant seat in the Hall of Justice auditorium. I had expected, with all the advertising, there would be more women, but only about one in ten of the test takers was female. Some were older people who’d been forced into second careers by the economic downturn, but most looked about my age, young and eager.

We watched hours of brain-numbing videos depicting ficti- tious crime scenes, then answered hundreds of multiple-choice questions. The test focused on our observational skills and ability to recall details. No actual knowledge of the law was required. It seemed fairly straightforward, and I was confident I’d done rea- sonably well.

The agility test had me more nervous. I wasn’t sure what level of physical fitness was expected or how stiff the competi- tion might be. To be on the safe side, I decided to attend the free training offered by the city.

The training class met in the evening at the Hall of Justice gym. The two female officers in charge were attractive and very fit.

I’ll call them Thelma and Louise. The group of fifteen academy hopefuls, all women, varied in age and fitness. While I was not particularly sporty, I had done weight training in college and was strong. If you created a fitness chart with the Pillsbury Dough- boy on one extreme and a Navy SEAL on the other, I would have fallen somewhere in the middle.

The agility test consisted of an obstacle course where we were to run a few laps around the gym, hop onto a low balance beam, run along it without falling, jump over a six-foot wall, drag a 150-pound dummy-shaped sandbag fifty feet, and hoist the dummy onto a low table, folding his arms and legs over him. Finally, we would take a grip-strength test. The whole event was timed, and we would be ranked according to speed.

Louise started us working on the dummy drag first. I tied my long hair back in a ponytail and hoisted the dummy under his armpits without much effort. I hauled him across the room, heaved him on top of the platform, and folded his legs in record time. I nodded in satisfaction. Months of toting trays of fishbowl-sized margarita glasses and manhandling drunken customers had paid off.

The wall was another story. I had never before attempted to hurdle myself over a six-foot wall, but after displaying my superior dummy-dragging skills, I was a bit full of myself. I got in line for my turn. So far, no one ahead of me had made it over.

The wall was a smooth, solid hunk of golden wood. Its glossy, shellacked finish offered no footholds or traction.

When my turn came, I ran to the wall and jumped to grab the top as I’d seen the others do, but I struggled to pull myself all the way up. Hanging there, feet dangling uselessly, I tried again and again to haul myself over. Finally I surrendered and dropped to the floor like rotten fruit. I watched as the women in line behind me also failed. We each took our turn. We jumped, hung, gave up, and dropped. After each turn, we whined, groused, and commiserated.

“This wall is too high! This wall is too slippery! This wall is sexist! This wall hates people who have breasts!” I wondered if the naysayers were right. If I couldn’t even get over this wall, maybe I didn’t deserve a spot in the department.

Thelma and Louise had been watching us do our routine for some time without comment.

“You girls can get your asses up over that wall just as fast as the guys can,” Thelma finally said. We looked at each other, skepti- cally. “You just have to know the trick. Women can’t do things the same way men do. Our strength is in our legs, ladies. Thunder thighs! There’s a reason why God gave us big muscles in our legs.” I then noticed Thelma’s firm, well-defined thighs, the approxi- mate size and shape of HoneyBaked hams. “I want you to watch very carefully how I do this. Later, I’ll do it in slow motion, and that’s the way you’re going to start: real slow. Then you’re going to practice a hundred times a day until you can get over that wall in three seconds. You hear me?”

We nodded pessimistically, still not convinced the wall was scalable.

“When I say, ‘You hear me?’ you say, ‘Yes, ma’am!’ You hear me?” We answered together. “Yes, ma’am!”

“That’s how it’s gonna be if you ever get your sorry asses into the academy. ‘Yes, ma’am’ and ‘Yes, sir!’ You got that?”

“Yes, ma’am!” we replied. A joker behind me said, “Yes, sir,” but Thelma missed it.

Thelma then ran to the wall full speed, leaped, and grabbed the top deftly while simultaneously planting her right foot in the middle about three feet up. Throwing her left leg over, she bounded off in pursuit of her imaginary criminal. A jump, climb, swoop combo.

“Go get him!” yelled Louise. “Get that bad guy!”

Watching Thelma, I suddenly saw there was more than one way over that wall, and I knew I could do it too.

“Girls, I want you to remember this. In the academy you are going to have to master many skills. Men will teach you these skills and the ways they do them. You are not men. Sometimes you are going to need to find your own way to do things. Some- times, your way will be even better than their way.”

She and Louise spent the remainder of class breaking the steps down slowly. Jump, climb, and swoop. Jump, climb, and swoop. It took us many tries that night, but by the end of class we had all mastered the wall.

When test day finally came two weeks later, the wall was a cinch. I jumped, climbed, and swooped. It amazed me that I could climb over it in seconds.

The third challenge was the oral exam. When the day came, I couldn’t decide what to wear. It hadn’t occurred to me to invest in a decent suit, and I hadn’t thought to ask anyone what women wear to such interviews. I finally settled on a gingham dress and black four-inch heels.

Unlike the agility test, I’d done nothing to find out how the oral exam would actually be administered. I had, however, mentally planned the entire thing, imagining the questions the board would ask, and although no one had told me to do so, I’d prepared a fifteen-minute speech about why I would be a great police officer.

I was seated before a panel of three men whose faces revealed none of the milk of human kindness. My outfit had seemed ade- quate as I dressed that morning: business-like, but feminine. But now, before these men, it felt ridiculous. The dress’s neckline was embarrassingly low, and I’d worn too much lipstick and my long hair was loose.

A few minutes before I walked into the room, a monitor handed me a scripted scenario involving a dispute between neighbors. One neighbor was displaying a swastika poster in his front window. The other neighbor wanted the poster taken down. Every time I told the interviewing sergeant that I would ask the offending neighbor to take down the poster, the sergeant replied, “He’s not doing it!”

When I suggested the complaining neighbor could live with it, the sergeant screamed, “He wants it taken down!” I had no idea where the law stood on this issue and could think of no alternative solu- tions. I mentally reviewed First Amendment rights, not knowing if the police could force a citizen to take down an offensive sign.

The whole time, I resisted the urge to tug at the lacy fabric near my neck and stretch it to cover my cleavage. Why had I thought playing up my femininity was a smart idea? These men wanted to see a man sitting in front of them, or at least someone dressed like a man. I felt exposed, like they were giving me a gynecologi- cal exam without even supplying me a paper gown.

My fifteen minutes finally came to an end, and I never had the chance to tell the board a word about why I’d be such a great cop. I left knowing the only way I’d make it into the academy was if I had a high enough score on the written and agility tests to make up for this disaster. I skulked down the stairs of the old hospital, certain I’d failed.

A few weeks later, I opened an envelope with a return address from the City and County of San Francisco. The hiring list had hundreds of names ranked by overall score. While I was far from the top, I’d scored enough cumulative points to be in the hiring pool and would move on to an academy class when they reached my number.

Knowing Mom would be furious, I avoided telling her for months as the city worked their way down the list and finally reached my number. Two weeks before my academy class was due to begin I worked up the nerve to call. I braced myself to deliver the news. No matter what awful things she said or did, I held out hope for our relationship.

“Hi, Mom. How are you?”

“OK, I guess. John still sits like a lump all day,” she said, speak- ing of her current husband. “Honestly, I don’t know what I was thinking, marrying an older man. He has no sex drive whatsoever.”

I’d heard this complaint before and rapidly changed the subject before she volunteered grisly details. “Yes. Well, I have some good news.”

“Let me guess, you’re getting married,” she said, without enthusiasm.

“Well, no.” I worked to keep my tone upbeat. “I’ve decided to join the San Francisco Police Department. They’re doing a big hiring drive and opening the doors to women.”

“Are you out of your mind?” she shrieked. “How could you even think of joining them after everything they’ve done to me? They’ve been persecuting me for decades! I knew you hated me, but this is the worst thing you’ve ever done to me! Why not just

drive a stake through my heart?” I took a deep breath.

“Mom, this is not about you. It’s just something I have to do.”

“Well, isn’t that the world’s greatest news! My daughter’s becoming a fucking Nazi!” She slammed down the receiver without saying good-bye.

I sank onto the couch. Maybe I was being crazy. Why did I want this so badly? Why had I worked so hard to put myself through college, only to subject myself to the police academy? Was I doing all this to rebel against my mother? No. That was ridiculous. Then I considered everything I’d been through with Mom, and the answer was obvious.

My whole childhood, Mom had been training me to be a cop.

To purchase this book go to

http://astore.amazon.com/winwomandcho-20

Hi I’m Catherine, founder of Wine Women And Chocolate. Want to become a contributor for Wine, Women & Chocolate? Interested in sharing your unique perspective to a group of supportive, like-minded women?

Hi I’m Catherine, founder of Wine Women And Chocolate. Want to become a contributor for Wine, Women & Chocolate? Interested in sharing your unique perspective to a group of supportive, like-minded women?